Writing Systems #1 - Punjabi

Not so long ago was the celebration of Lohri, which hails from Northern India and historically from the Punjab region and as a result, Sikhs and various other faiths have celebrated this day for centuries.

The day, Lohri, is the winter solstice (shortest day) in Northern India and the celebration is meant to see the end of bad times and welcome in good times and the spring. People tend to give prayer, eat a lot of food, and have fires to cleanse themselves for an upcoming season of harvest. I myself am a Sikh, which is why I know about Lohri, and our predominant language in Sikh faith is Punjabi – which is what I am going to be talking about today in the first part of a two-part Punjabi-Gurmukhi-themed blog.

Punjabi is a very different writing system to the ones used in Europe and instead of being alphabetic or syllabic in nature, it appears like a concoction of both. Alphabetic writing systems include ones in Europe such as Cyrillic (such as Russian), Greek, and Latin (the alphabet you’re reading in), where the graphemes (letter or combinations of letters) correspond to a particular phoneme (a sound stored within the brain). Syllabic (or moraic) writing systems such as Hiragana, Katakana (both Japanese Kana), and Cherokee are where graphemes correspond to a syllable (or mora) which is made from an onset and a nucleus which essentially means a beginning sound and a middle (usually vowel) sound. One represents a sound per letter, the other represents a syllable and thus multiple sounds per letter.

Punjabi has elements of both of these writing systems and at first glance, it seems quite complex – I personally believe it to be very efficient and easy, but that could be because I have grown up with it. Whilst it has graphemes that can be considered letter and specific elements that make particular phones, each of them also builds to form a syllable. Punjabi’s writing system is known as Gurmukhi and is a type of writing system known as either an alphasyllabary (an apt name considering it is a hybrid system between the two), or an abugida. Another famous abugida would be Hangul, which is Korean’s writing system whereby syllables are built from subletter elements.

Gurmukhi has a total of forty-one graphemes, thirty-five of which can be described as the primary syllabary. Of these, only three of them are vowels, the rest are all consonants. The main syllabary tends to be arranged in a grid of seven lines each with five graphemes. Often, five out of six of the extra graphemes (or special letters) appear as a final eighth line and sometimes even the sixth special grapheme is included in a line of six at the end. This sounds all a little like rambling, but the special letter that is missed out often is always the same one missed out. The rest of the five special letters all have something in common with each other from a phonetic point of view as does the rest of the Gurmukhi abugida. The only lines that don’t follow the rest are the first and final lines (and the extra line), but even then, all of the elements in those lines have their similarity.

Before continuing, I’d now need to delve into the IPA (for those of you that have read my previous linguistics series, you would have seen that coming). That doesn’t stand for Indian Pale Ale for anyone who’s spirit animal is a middle-aged bloke, it stands for the International Phonetic Alphabet. The IPA is a very useful system that allows all spoken sound to be converted into a totally unambiguous system of notation where one grapheme (letter) always corresponds without fail to a unique phoneme (sound).

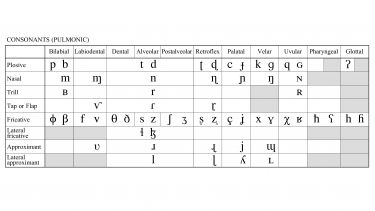

The IPA is arranged into subgroups of phoneme types – vowels have their own trapezium, and pulmonic consonants have their own grid. On this grid, there are all of the known consonants that are able to be produced pulmonically (where the lungs are the mechanism for their production) across all languages. The columns denote the specific place of articulation of these phonemes, and from left-to-right, the places of articulation range from most exterior (which are bilabial sounds such as /p b m/) to most interior (which are the glottals such as /h/). The rows are divided in a similar way, but not by place, instead by manner of articulation – the way in which the sound is produced. Is the sound a harsh plosive? Does it continue? The range from top-to-bottom is in order of openness within the vocal tract. Plosives demand complete closure, whereas the approximants leave great spaces within the oral tract and are sometimes referred to as vowels in some languages. Below shows the pulmonic consonant grid of the IPA. The pairs show sounds which share identical manner and place of articulation but differ in voicing such as the difference between /p/ and /b/ - the right-hand component is the always the voiced one. The white areas show places that currently do not have known sounds of meaning in any language but are nonetheless deemed possible to produce. Finally, the grey spaces are those sounds judged impossible to make.

This might not sound all that interesting, but the way in which it is ordered is thought about with great precision, debate, and laden with research – hence the international part of this phonetic alphabet’s name.

The first line of Gurmukhi contains the only three true vowel graphemes, and in the latter part of the line, the only two fricatives of the primary Gurmukhi orthography. These two groups share one thing – all of them are continuing sounds. The final line of the Gurmukhi syllabary comprises of three approximants (one lateral and two central), one tap, and one flap. These are, again, all continuing sounds from two other rows of the grid above. The extra line of six sounds contains five fricatives, which seem absent from the alphabet, and are normal graphemes from the main syllabary with an added tittle (a little dot) to represent their difference from the regular grapheme. The final thing to note is that the regularly omitted sixth letter is not from the same class of sounds and is a retroflex approximant – this could be why it is often left out or just added at the very end.

So that’s still not saying much is it? Here’s where it gets a little more interesting. The roots of Punjabi are based in an area of great civil and territorial unrest over the centuries that has long pre-dated Sikhism itself. The people of the Punjab region have spoken Punjabi for many years, and those with a keen cultural or linguistic knowledge of India should know that Indian is not a language. It isn’t even a language family, that word (known as a demonym) would be Indic. There are seventeen native languages to India, and of them, there are fewer scripts because historically, the juggernaut language of the area, being Hindi, has often been adopted for the smaller languages that were without writing systems. So, there are seventeen languages at least, but far fewer writing systems. The Hindi script, known as Devanagari, was often adopted for Punjabi as for centuries previous, it went unwritten. Due to large surrounding settlements of Islamic communities within and around the Punjab region and rising tensions between Muslim and Hindu empires, people of Muslim faith began to use Shahmukhi, which is a variation upon Urdu and Arabic scripts. The political tensions caused such a divide between faith boundaries, one major faith used Devanagari, and the other used Shahmukhi.

Devanagari is an abugida as well and was used to represent the Hindi tongue, which has a great deal of overlap to Punjabi in many regards, though as the two are separate languages, there are enough grammatical differences between the two. Shahmukhi is an abjad, another type of writing system, and this did not encapsulate all of the phonetic information that Punjabi speech presented. The emergence of Sikhism with its second guru, Guru Angad Dev Ji, allowed for a new opportunity. One with an even more efficient alphabet with sole regard to Punjabi pronunciation and phonetics. One that could be used by anyone in a new and growing faith. The second guru devised his own partly alphabetic, partly syllabic abugida system for Punjabi known as Gurmukhi…

Next time, I’ll actually go through how Gurmukhi is written, why Punjabi is efficiently ordered from a phonetic point of view, and I’ll show you what it looks like too…

Written by DP, Digital Student Ambassador, on 20 January 2022.