Misogynoir #1 - Intersectionality

In recent years, the conversation about race and white privilege has become more centralised as people are rightfully engaging in the discourse surrounding the historical and modern-day marginalisation of black people in the Western world.

Misogynoir

Books such as Why I’m No Longer Talking to White People About Race by Reni Eddo-Lodge, White Fragility: Why It's So Hard for White People to Talk About Racism by Robin Diangelo and White Allies Matter: Conversations about Racism and How to Effect Meaningful Change by Yanisha Parmar and Aseia Rafique have all been flying off the shelves as people rightfully wish to understand how they can enforce positive change and understand the uncensored history of black liberation and strife. However, alongside race discourse, little conversation is had regarding how marginalisation takes many forms and can impact groups of people twofold. That is how race and misogyny often intercept and how the experiences of black women are often overlooked.

Anti-blackness manifests itself in many forms and showcases itself in different aspects of everyday life; a person’s gender, sexuality and physical abilities are all aspects that can further marginalise them. Kimberlé Crenshaw coined the term ‘intersectionality’ as a way to define the particular forms of oppression black women face, but that term was adopted to define the experiences of people of multiple identities. In recent years, author Moya Bailey coined a newer term, ‘misogynoir’. Misogynoir, as Bailey stipulates, is the ‘specific hatred, dislike, distrust, and prejudice directed toward Black women.’ Misogynoir focuses on black women as the victims of race and gender-based oppression, as they occupy a unique position in which they are vulnerable to the oppression of both race-based violence and gender-based violence.

Misogynoir is an important topic to understand and become educated on because, statistically, black women are often overlooked in conversations about black struggles and experiences. As a black woman myself with the opportunity to use my words for the good, I would like to demystify the term and spread light on the experiences black women face and the oppression we face both outside and within our communities. My perspective does not speak on the behalf of all black women as we are not a monolith, however, a lot of what I will be writing about resonates with a lot of black women.

Black Women, Feminism, and the Need for Intersectionality.

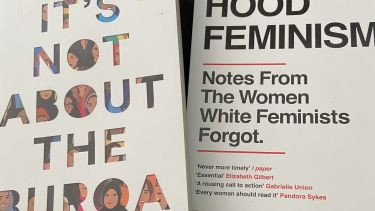

In one of my favourite critical race theory books, Hood Feminism, Mikki Kendall writes, ‘my grandmother would not have described herself as a feminist… she did not think of white women as allies or sisters.’ This statement from Kendall is expanded upon as she goes on to explain that her grandmother and many black women of her time did not consider themselves feminists or align themselves as sisters-in-arms with white suffragette women because the early feminist movement did little to improve her life. Her grandmother worked, as all women of her race and circumstances did. For many like her, being confined to household work seemed like a privilege to her, rather than oppressive. Kendall goes on to explain that despite not aligning herself with feminist movements, she lived her life in accordance with feminist principles - she educated her daughters, she worked

and she lived independently. So why did her grandmother not align with feminism? Because that type of feminism did not serve her. In recent years we have coined the term ‘white feminism,’ to describe the type of feminism that is pioneered by white feminists but does little to support the lives and experiences of women of colour. White feminism ignores the fact that women of colour experience the world differently and therefore have specific needs based on these circumstances.

The early feminist movement fought for the right for women to vote, but only the right for white women. Black suffragettes were a thing, and a piece of history that is often overlooked or ignored as the early suffragettes purposefully ignored black suffragette leaders. Widely appraised for their efforts in landing women the vote, Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Stanton are two names that are continually honoured, however not many know that Anthony and Stanton actively ignored the pleas for support from black female liberationists. When they were barred from voting in the south, black liberationists looked towards the two women for support but were instead met with refusal. Historian Lisa Tetrault states, that when met with these pleas, the two women regarded the issue as one of race and refused to intercede. To this day, this replication of feminism ignoring the plights of black women recycles itself as black women’s experiences are often ignored by white feminist movements or grouped in a collective narrative of struggle. Early wave feminism did not include black women, it did not serve them.

Therefore, to rectify the issue that early feminism created, the way forward for the movement is intersectionality. Intersectionality acknowledges that multiple different circumstances impact a woman’s experiences with oppression and marginalisation. Feminism without recognition of the real and valuable lived experiences of women of colour, transgender women, women who identify as LGBTQA+, women with disabilities and women of lower-socioeconomic backgrounds cannot achieve its purpose. Intersectional feminism places the needs of those in precarious or vulnerable positions above those of the privileged; immigrant and refugee women and homeless women are often overlooked as groups of vulnerable people who need support and help. Many say that the feminist movement is not necessary for the modern age, but this is a factious statement, it largely ignores the pleas for help from women in poorer countries and dire situations. The work of feminism has only just begun.

Books I Recommend: Race Theory

● Misogynoir Transformed: Black Women’s Digital Resistance by Moya Bailey

● Hood Feminism: Notes from the Women White Feminists Forgot by Mikki Kendall

● It's Not About the Burqua by Mariam Khan (Where Raifa Rafiq’s essay is written, includes some incredible essay pieces from Muslim women)

● Black Tears, Brown Scars: How White Feminism Betrays Women of Color by Ruby Hamad.

Written by Valentia Adarkwa-Afari, Digital Student Ambassador, on 8 April 2022.

Experience Sheffield for yourself

The best way to find out what studying at Sheffield is like is to visit us. You'll get a feel for the atmosphere, the people, the campus and the city.