Roland Barthes, Park Hill Flats and the Death of the Author

On how Park Hill graffiti can help explain why there is an art to literary criticism.

Writing is that neutral composite, oblique space where our subject slips away, the negative where all identity is lost, starting with the very identity of the body of writing. […] As soon as a fact is narrated no longer with a view to acting directly on reality but intransitively, that is to say, finally outside of any function other than that of the very practice of the symbol itself, this disconnection occurs, the voice loses its origin, the author enters into his own death.

Roland Barthes

The Death of the Author

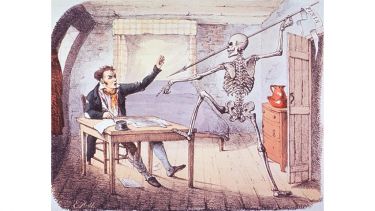

And so, in this (not uncomplicated) passage first published in 1968, Roland Barthes announced the death of the author. I’ve found that it always comes as a shock to students when I tell them that literary criticism killed off the author in the 1960s. Often they are grieved by the news; some quickly move through cycles of confusion and denial while others sit quietly, humbled by the implications. They are even more shocked when I tell them that not only has the author been killed, but that I’m glad they’re dead.

I’ve often grasped for Barthes in seminars — in situations where free-flowing discussion is at risk of being shut down by sensible individuals who realise “this might not be what the author meant”, it can be handy to remind everyone that it doesn’t matter, the author is dead. But I’ve never been faced with the challenge of teaching Barthes’s essay…until this semester. It is a tremendous piece of writing and returning to it now I am more astonished than ever by what a fine and influential essay it is. In fact, the implications are so many, and so complex, that I was actually quite unnerved by the prospect of trying to teach it in a seminar. Fortunately serendipity and the interconnectedness of all things saved the day, when a BBC Radio 4 documentary about graffiti in Sheffield’s Park Hill flats was brought to my attention (BBC Radio 4, The I Love You Bridge), presenting me with an analogy so fruitful I felt it simply had to be shared.

Of course, no authors have actually been killed in the making of this blog post. Both Barthes and I are referring to the figure of the author: the “author function.” It is often the case that when a student first sets out into the world of literary study they find themselves trying to decode an author’s intent: what did the author mean when they wrote this? How does this map onto their life? What can this text tell us about the author? I know this because I did exactly the same thing — and these are important questions. Barthes considers this and asserts that authorial intent has previously been a large part of the critic’s job:

To give a text an Author is to impose a limit on that text, to furnish it with a final signified, to close the writing. Such a conception suits criticism very well, the latter then allotting itself the important task of discovering the Author […] beneath the work; when the Author has been found, the text is ‘explained’ – victory to the critic.

Roland Barthes

The Death of the Author

Approached thus, the literary text becomes a piece of biographical evidence (i.e. Wyatt wrote this because he was disenchanted by courtly life… Pope wrote this because he’d seen similar events take place in a Salon… Goldsmith wrote this because he was worried about hedges…) and a quest begins for the definitive interpretation. Barthes goes further, however, and dares to ask what might happen if scholarship abandoned the idea of intended meanings laid down by an author. What happens if it is not the author who prescribes meaning, but the reader? Thus he reveals the complex make-up of writing:

A text is made of multiple writing, drawn from many cultures and entering into mutual relations of dialogue, parody, contestation, but there is one place where the multiplicity is focused and that place is the reader, not, as was hitherto said, the author. The reader is the space on which all the quotations that make up a writing are inscribed without any of them being lost; a text’s unit lies not in its origin.

Roland Barthes

The Death of the Author

Barthes successfully shifts the emphasis from the author to the reader—and that’s us. The literature itself becomes a stimulus; the clay from which we will fashion our own interpretation… But what does any of this have to do with Park Hill flats?

Designed in 1945, Park Hill is an enormous housing construction built to house a thousand flats, prominent on the Sheffield skyline. The architect built them around an exposed concrete frame with yellow, orange and red brick curtain walling. Within these walls there was originally a shopping precinct and a primary school, and the site became renowned for its bridges (optimistically referred to as “streets in the sky”) which were wide enough for milk floats. However, time has not been kind to the flats — the city council regarding them a “drab, grey, dilapidated” thing — and it caused a controversy in 1998 when English Heritage decided to make them into Europe’s largest listed building.

The flats loom over the city, looking down on the station and Sheaf Square. Written in paint on one of the bridges are the words “I love You will u marry me.” This message, which is visible for miles, has become iconic throughout the city and beyond. Historically the graffiti has been anonymous, prompting much storytelling and speculation as to both who did it and how it was achieved. It has been the subject of art, it has appeared on t-shirts (notably those worn by the Arctic Monkeys) and it has provided the title of a single by popular local band, The Crookes. To commemorate Park Hill’s fiftieth year, Urban Splash (the firm restoring the estate) decided to immortalise the message by tracing it with a neon sign as an "invitation to the city".

However, if you look closely at the bridge, you can just about make out a few more words. The original graffiti in fact reads: “Clare Middleton I Love You Will You Marry Me.”

By omitting to highlight the addressee in neon Urban Splash claim to have transformed a public declaration of love addressed to one individual into a universal message addressed to the public. It creates for the city what Penny Woolcock lyrically describes as “an optimistic message of love blazoned across this vast dilapidated building.” The author’s intention becomes redundant. The message is appropriated and applied by/to a second party. Its meaning is changed. The author function is dead.

Discovering the identity of the author (and of the original recipient, Clare Middleton) becomes the business of Penny Woolcock’s recent BBC Radio 4 documentary; and along the way she highlights the significance of both the author function and its dismissal.

Woolcock arrives in Sheffield with the intention of finding both Clare Middleton and her suitor, keen to uncover a deeply romantic tale which she has clearly already written in her mind. Whilst regaling listeners with apocryphal stories concerning Park Hill’s troubled past, she makes no secret of her romanticised ideal of the bridge. “You look at the estates, and you think ‘how can people have lived like this?'”, she asks. Her response? “The answer is the ‘I love you bridge’, that’s how people live, with love.” Woolcock shares with listeners the way she imagines the message must have been written, with the author dangled over the edge by an accomplice.

A few brief exchanges with local residents reveal she has not been alone in creating such mythologies. Everyone has a different tale to tell of how the message came to be. The two were very much in love, but they each died, one resident explains. He was involved in a gang, another goes on, describing the bridge as being “like Romeo and Juliet, but in concrete.”

After some intrepid reporting Woolcock successfully tracks down the lovers, but in retrospect concedes her findings confounded all expectations: “We thought it was going to be quite a lighthearted little piece”, she explained in The Guardian. The author (whose name is Jason) comes forward, revealing that not only did the pair not get married (“things went wrong”, Clare’s mother explains), but Clare passed away following a period of life described in the documentary as “chaotic”, “daft”, and marred by “problems” involving “drugs and social services.” Jason remembers her fondly. “There was something about her. She had really deep brown eyes, it was her mystical brown eyes”, he recalls: “She was a very loving person.”

Woolcock is presented with a rare opportunity to ask the author figure how he feels about Urban Splash’s decision to adapt, appropriate and erase his words. He’s not impressed by their decision not to highlight Clare’s name: “You can’t leave one off without another, it was written as one purpose”, he says. “If they’re gonna keep it, they’ve gotta keep all of it. This wasn’t to anybody this was wrote specifically for Clare.”

Jason is far from the first to have his work appropriated by others in a way that does not match or further his original intention. For instance, this speech given by John of Gaunt in William Shakespeare’s Richard II has often been employed patriotically as a nationalistic celebration of England:

This royal throne of kings, this scepter’d isle,

This earth of majesty,this seat of Mars,

This other Eden, demi-paradise,

This fortress built by Nature for herself

Against infection and the hand of war,

This happy breed of men, this little world,

This precious stone set in the silver sea,

Which serves it in the office of a wall,

Or as a moat defensive to a house,

Against the envy of less happier lands,

This blessed plot, this earth, this realm, this England,

This nurse, this teeming womb of royal kings,

The following section — which reveals John to be nostalgic for such a time while anxious that this greatness has suffered a recent decline — is often unquoted in such citations:

This land of such dear souls, this dear dear land,

Dear for her reputation through the world,

Is now leased out, I die pronouncing it,

Like to a tenement or pelting farm:

This second passage reveals the paradise described above to be an illusion. Rather than a celebration of England’s greatness, it becomes a meditation on greatness lost. Omitting these final lines changes the speech entirely. Shakespeare’s words are adapted to new purposes, just as the meaning and addressee of Jason’s graffiti is altered. The author, it transpires, is without authority.

But is this a bad thing? If anything Woolcock’s documentary also reveals the reductive damage that the rediscovery of the author can do to an interpretation. Before meeting Jason, Woolcock has created (in response to the graffiti) an optimistic tale of love conquering all. This is hers. On finding Jason and discovering his alternative tale, she is confronted with tragedy. She imagined the author dangled over the bridge by his ankles by an accomplice, risking life and limb to make an unabashed gesture of love. Instead she finds that Jason was drunk, depressed by Clare’s reticence, spurring him to lean over the bridge as far as he could. She suggests there is meaning to be found in the fact that Clare’s name has always been less clear, less prominent, than the rest of the proposal. She speculates that these words are “the ghostly trace of Clare Middleton […] fading into concrete.” Sharing this lyrical idea with Jason, he audibly shrugs and adds pragmatically: “Well, I probably just didn’t shake the can enough for that bit.”

But none of this detracts from Woolcock’s reading of the graffiti. Setting aside this history of inscription, Woolcock’s reading remains enlightening; it still has something to tell us about love, optimism, romance and human nature. Jason merely provided the stimulus for a reading that Woolcock creates, and this is a perfect analogy for the relationship between the author and critic. Interpretation — the business of seminars, articles, monographs and adaptation — is a creative enterprise. When he inscribed his message on a public space, Jason did more than propose marriage to Clare Middleton; he gifted the city with a stimulus. As Barthes suggests of the reader, it is the people of Sheffield who give the message meaning:

The reader is the space on which all the quotations that make up a writing are inscribed without any of them being lost; a text’s unity lies not in its origin, but its destination.

Roland Barthes

The Death of the Author

To escape the urge to seek authorial intention is to enter into the realms of interpretation; meaning is created when the text meets the reader, making the job of the literary scholar a creative — rather than a speculative — activity.

So the author (function) is dead, and that’s probably for the best…Discuss.

Written by Adam J Smith on 26 September 2013