Mozart: Music’s greatest freelancer

Remembered as a child prodigy, how did Mozart craft the masterpieces that would remain well known over two hundred years after his death? Research from the Music Department has unearthed a new side to the musician that involves re-working pieces to please all audiences.

Recognised as one of the greatest classical composers of all time, Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart composed more than 800 pieces of music throughout his short life. Before his death at the age of 35, he had showcased his versatile talent by producing music across a wide range of genres such as chamber music (instrumental music played by a small ensemble) and opera.

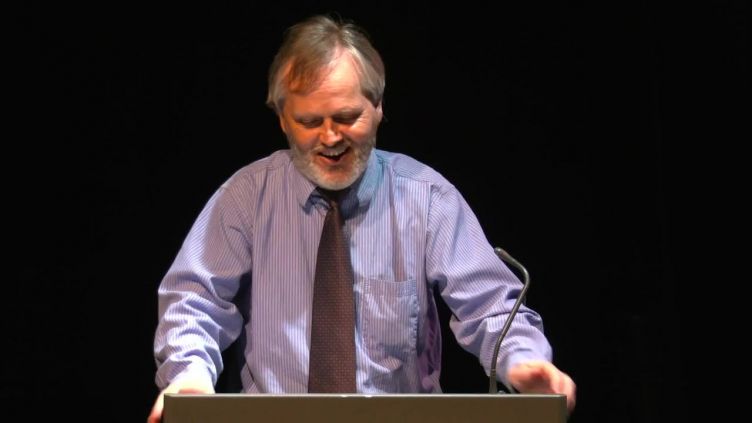

Research by Professor Simon Keefe from the University of Sheffield’s Department of Music suggests that rather than constructing a perfect piece of music Mozart regularly made adjustments to his existing music for different performers and venues.

Professor Keefe studied Mozart’s manuscripts, the original handwritten music pieces, to reveal hidden layers of corrections and changes that were made to cater to specific audiences and performers. His study also provided insight into Mozart’s busy life as a touring musician and performer.

Putting pen to paper

A talented composer and performer from a young age, Mozart mastered a minuet and trio (today, a grade 4 musical piece) on the piano as a toddler and wrote his first opera at the age of 12.

The prolific years in his twenties would shape 18th-century classical music and make him a household name as a child prodigy and genius. But through comparing Mozart’s hand-written musical documents with their first published editions, Professor Keefe found that his ability to create perfectly-chiselled works with minimal effort is likely to be a misconception.

“The working assumption for Mozart was that he wrote all of his work fluently without ever making a mistake. It was said that he would create musical pieces in his head and release them on paper in a divine way, almost like an effortless compositional exercise. Although this gift is witnessed in many complex compositions, where few if any changes were made, it was not always the case. In recent years, a number of academics, including myself, have challenged the notion of Mozart writing primarily in a flawless fashion, and thereby explain his compositional process as significantly more complicated than is often assumed - including in the 'Haydn' quartets” explains Professor Keefe.

The Haydn quartets

Joseph Haydn was also an Austrian composer during the 18th century and grew to prominence by establishing the style of the string quartet (an ensemble consisting of two violins, a viola, and a cello) and the symphony (a full orchestra, typically in many parts).

Although their first meeting is undocumented, it is believed that their friendship began when Haydn, aged nearly twenty five years older than Mozart, was already an acclaimed composer of the time and Mozart was still gaining popularity.

Mozart dedicated six of his string quartets to Haydn, the most esteemed composer at the time.

“Haydn is a figure who often appears in writing about Mozart and vice versa. The British Library owns the manuscripts of the Haydn quartets, and they have all been digitised. The scans are high quality and you can zoom in easily to see Mozart’s minor modifications to his work, such as smudging ink with his finger to make a quick change to the music, rather than properly redacting it. The manuscripts would have been a working document and it is likely that additional dynamic markings were added after hearing the piece being performed as it would show where performers needed more direction” explains Professor Keefe.

“The six string quartets were developed over a three year period, which is very long for Mozart. During that time, we know he wrote lots of other music, but works such as piano concertos were written more quickly because he needed them for particular concerts. It was only late in this creative process that he decided to dedicate the quartets to Haydn” he adds.

A common misconception is that the reason why Mozart spent so long constructing Haydn’s quartets was to perfect them and please his friend. But it was through studying these particular works that Professor Keefe discovered that Mozart’s experiences of his works in performance affected the final product. By these calculations, the quartets were not just an abstract exercise to please Haydn as previously thought, they were more than that.

The history of talking about Mozart's Haydn quartets involves talking about how wonderful they are as works of art. In other words, they’re beautifully conceived and executed and I don't deny that, but they also capture his experiences as a performer and his thinking as a performer, which altogether, is a new way of thinking about Mozart and his work.

Professor Simon Keefe

James Rossiter Hoyle Professor of Music and Musicology at the University of Sheffield

A performer’s best friend?

A combination of talent, commitment to the craft and attention to detail is evident through the alterations to the manuscripts. Mozart’s intent to alter his pieces of work based on his experience as a performer, as well as a composer, suggests that he had considered his audience’s immediate reactions more than we originally thought.

As a composer, Mozart created his work for primarily three kinds of audiences; himself, specific performers that he knew personally and for faceless, unknown performers he would reach through publishing houses.

“When Artaria, the Viennese publishing house, took on Mozart they had to think about whether his works would sell. In those days, the publishers would pay an upfront fee to the composer and that was all that they would receive as royalties did not exist. It was in everybody’s interest to make these works as sellable as possible. Mozart realised that by creating pieces that were accessible to performers he would be able to sell more. He didn’t have the time, energy or inclination to abstractly think about musical perfection - he had to think about work that would sell” says Professor Keefe.

“Part of making it a work that would sell was to engage with issues surrounding and connected to performance because connecting to the performer would make the performer want to buy the musical publication. Based on my research, it is clear that practicalities and pragmatics entered the equation for Mozart when creating these works” he adds.

When creating work for musicians in his inner circle, changes to the manuscripts suggest that his work was adapted to the strengths of the performers, improving the experience for the audience.

Bringing the research to life

Manchester Camerata is a British chamber orchestra ensemble and charity established in 1972. In May 2021, Professor Keefe led an exclusive, lecture-led live stream to illustrate how the 'Haydn' quartets changed as Mozart perfected them over the years. Collecting several ‘before’ and ‘after’ examples, the performance showed the differences between Mozart’s original manuscripts and the published version of the works, providing an insight into the composer’s unvarnished thoughts prior to alterations for the performers.

Manchester Camerata showcased the changes by performing complete renditions of the famous works, allowing a modern audience to compare passages for the first time.

Video credits: Violin 1 – Caroline Pether, Violin 2 – Will Newell, Viola – Alex Mitchell, Cello – Hannah Roberts.

“The acoustics of the Drama Studio at the University were perfect for hearing even the intricate differences in the versions. The Concerts team did a fantastic job in organising a hybrid event. By performing these pieces live, the audience was able to experience the ‘Haydn’ quartets in a different way and observe how they evolved as Mozart shifted between seeing himself as a composer, and then as a performer” says Professor Keefe.

The University of Sheffield’s Department of Music is one of the UK’s leading centres for music research in the UK.Researchers in the department are at the cutting edge of studies in areas such as composition, ethnomusicology, musicology, music technology, performance and the psychology of music.

Written by Alina Moore, Research Communications Coordinator