The House of Help: Sheffield's home for 'friendless girls'

MA students in the School of English are provided with the opportunity of taking a work placement as part of their degree programme. This year, James Throup is working at Sheffield Archives and Local Studies Library as a social media assistant.

As part of James Throup's work placement, he is writing a series of blog posts highlighting the city’s fascinating archival treasures. This post first appeared on Sheffield Libraries’ blog on 11 April 2016.

Picture the scene: A summer night in Sheffield, 1889. Most of the city is thick with slumber. A few stragglers and stray revellers ghost the near deserted streets round Paradise Square.

In Oakdale House, the ‘House of Help’, all is quiet. Suddenly, a stern knocking at the door breaks the stillness of the night. A drowsy warden prises herself away from the soft embrace of sleep, grumbling but not too surprised, what with admissions coming at all hours. Even at 2am, like tonight.

The Police Constable drops off a young woman named Eliza Price. Eliza had been living with her sister ‘but has quarrelled with her and came to Sheffield’ where ‘she has been leading an immoral life but would be glad to go to a house’. The House of Help is willing to do what it can.

Initially established as a Free Registry in Fawcett Road in the late 1880s, the ‘House of Help for Friendless Girls and Young Women’ was an institution that provided aid for those in need. In later years, it was more often referred to as Oakdale House. The house closed in 2005.

The credo of the institution was ‘to give help and support to girls and women who are homeless and friendless’ (Hawson, 1985), but also to save them from immorality and vice.

A specific criterion was initially drawn-up to judge those worthy of admission:

- Young women who have fallen from virtue and desire to redeem their character.

- Young girls who have lost one or both parents or have living parents, should these parents be of loose character.

- Girls coming into the town by train, or otherwise needing temporary lodgings are received either day or night.

- Girls of good character, who are not able to go to situations for want of clothing are provided with outfits which are afterwards paid for.

- Help is given to friendless girls who have recovered from illness in hospitals and have been compelled to pawn their clothing.

- No girl or woman, being intoxicated or uproarious in conduct can be admitted at any time to this institution.

The house sought to bridge the gap for girls who wanted to improve their situation but lacked the necessary means to do so. Food and board were provided, as were clothes, and the opportunity to learn sewing, reading, and writing. Moreover, the house would also set the girls up with potential employers.

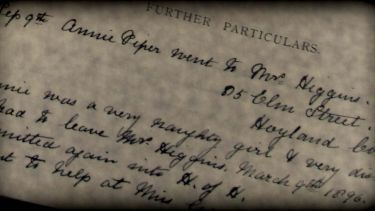

Leafing through the Case Books for 1888-1913, I was shocked to discover how young some of the girls admitted were, and how desperate their plights. Maria Moran appealed to the house of help on 13 August 1889, and was only 14 at the time. Her reason for application reveals a tragic tale of parental neglect:

"Came alone and begged for admission as she and the other children were neglected by their drunken parents… Had been living with her parents but was half afraid and almost naked and was often turned out at night by her parents and sheltered by neighbours."

Though she was received at St. Joseph’s Home on 24 October, ‘until some other arrangements could be made for her’, her parents turned up and reclaimed her; not long following, Maria appealed again to the House of Help. Many of the other cases follow a similar pattern, whereby the parents of young girls were unable or unwilling to care for their children.

Another tragic case is that of Emma Howard. Admitted on 27 March 1889, when she was 17, the reason for application reads:

"Has three married sisters in Sheffield but says none of them are respectable. A few days after her return to House of Help it was found she was subject to fits."

Consequently, she was ushered to a doctor, who ‘said that she was not likely to get better’.

Placed in a workhouse on 12 April 1889, she was later transferred to Wadsley Asylum. After spending time being shuttled back and forth between the workhouse and the House of Help, she gained a situation, but went missing from her last known address. Her entry closes by noting that she ‘left one evening saying she was going to the theatre and did not return’.

Cases like these are echoed throughout the history of the House of Help, going some way to indicate how myriad the problems were that resulted in girls seeking admission. Although in earlier years the focus was on prevention and rescue, particularly concerning those girls suspected of immorality, in later years the biggest problem affecting the house seems to be the high number of girls with mental health issues.

Whatever the problems facing the house, whatever the stories of plight brought before their doors, they were always willing to help out in whatever way they could – and for that their efforts should always be commended.

References

‘Residents’ Papers: Case Book 1888-1913’ Sheffield Archives: X158/5/1/1

‘One Hundred Years Forward: A century of the House of Help – Sheffield’s Oldest Hostel for Women’ (1985) Margaret Hawson, Sheffield Local Studies Library: 361.3 S

‘Annual Reports for the House of Help 1892 – 2003’ Sheffield Archives: X158/2

‘Photographs: Various [20th cent]’ in Sheffield Archives: X158/7

The Sheffield and District Family History Society have indexed the first six Case Books from Sheffield Archives. You can search their online index for names.

Written by James Throup on 9 May 2016.