Literature of the English country house: abolition, the slave trade and country houses in Sheffield

School of English graduate Jessica Yates, a researcher on the Sheffield Black Atlantic Project reflects on her extensive archival research for this project, demonstrating that this is very much a story with two sides.

1. Abolitionist culture in Sheffield

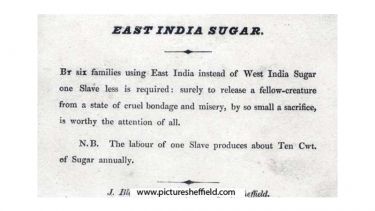

When delving further into the study of Transatlantic Slavery it became increasingly evident that Sheffield was a hub for abolitionist culture, generating an abundance of correspondence from people all over the country writing to or visiting well-known radicals. What is also interesting is the relentless perseverance of the people of Sheffield.

In fact, Joseph Gales had to leave the country due to the nature of the content of his radical newspaper, The Sheffield Register. Petitions were constantly sent to Parliament asking for the discussion of the abolition of slavery, but these were persistently knocked back. Additionally, Henry Yorke, along with many others, was tried for organising an open meet to drum up support for an anti-slavery petition sent to the House of Commons.

However, the biggest pressure for the abolition of the slave trade surprisingly came from the women of Sheffield. These women did not only strive to abolish slavery, but also tried to help those whose lives had been devastated by it. For example, the campaign of Mary Anne Rawson consisted of well-written poems depicting the hardship that slaves had to endure. However, the woman who sacrificed the most to help those affected by the slave trade was the Quaker Hannah Kilham. Kilham made several trips to West Africa and even set up a school for the young girls whose families had been torn apart by slavery. Her memoirs have provided a great insight into the fear of people living in West Africa.

From reading the pamphlets that were handed out by the many abolitionist groups in Sheffield, it seems that these women were trying to connect with people on every moral level. They mention that it is the duty of British women to protect those women bound by slavery and that as a Christian, allowing these things to happen is wrong. Often, the material that was published contained graphic and horrific stories to try and shock the public as people tended to turn a blind eye to the horrors that these slaves were subjected to. This was not helped by the fact that prominent religious and political figures were constantly trying to convince the British public that the slaves’ working conditions were similar to that of the British working class and that they lived a good life.

2. Cannon Hall and the slave trade

However, the story of Sheffield and the Transatlantic Slave Trade has a dark side.

One of the most interesting stories that I have come across is the ‘murky past’ of Cannon Hall. As the youngest brother, Benjamin Spencer identified that he needed to make a lot of money quickly as he was not going to inherit Cannon Hall. He therefore turned his attention to the slave trade and named the slave ship that he bought Cannon Hall. However, Benjamin’s inexperience soon showed as he did not fare well in this trade. Luckily, a lot of information about the ship (or Sloop) Cannon Hall is available as a lot of the letters received by Benjamin Spencer about his Sloop’s progress.

These letters document events such as how five slaves died on the voyage from Gambia to the West Indies. It is obvious that those running the Cannon Hall’s slave trade were either inexperienced or had ulterior agendas as maintenance of good health in the slaves was surely a priority. Additionally, the scale of the trade of the Sloop Cannon Hall was just too small to compete with those ships that were able to hold more than 300 slaves in one voyage. Amazingly, a rare piece of material relating to this topic exists, a slave collar has been recovered from Cannon Hall which is now held by the National Maritime Museum in Greenwich. On the other hand, after Benjamin’s death, Cannon Hall fell into the hands of Walter Spencer-Stanhope who was a staunch abolitionist and his close friend William Wilberforce even visited him at Cannon Hall.

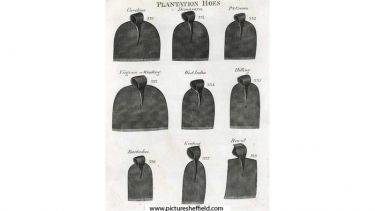

There is also a strong link between Sheffield’s industry and the slave trade. Sheffield manufacturers created the tools that built the slave ships and those that were used by the slaves on the plantations. Additionally, metal goods such as cutlery was traded with the African slave owners. In fact, the principal Sheffield steel manufacturer was Butchers Works, this still stands today, although it has been converted into flats, but was one of the last steel manufacturers in Sheffield’s city centre to be closed down.

These examples are incredibly fascinating as it makes this whole topic relevant and relatable. As a land-locked county, you would not imagine Sheffield to have such strong links to the slave trade but this surely proves how far-reaching the effects of this devastating trade were, and that if you look hard enough, these truly remarkable stories can be uncovered. The limited number of available resources that actually link Sheffield to the slave trade means that sometimes only snippets of information can be found.

However, this is completely understandable for two reasons: firstly, back then the slave trade was just a part of everyday life – it was not extraordinary, it was business. And secondly, the Black Atlantic Slave Trade is seen today as one of the greatest atrocities of the modern world and so it is unlikely that people will share information about how their families profited from it.

This post was originally published on the Storying Sheffield Blog, alongside another post on the topic.

If you are interested in finding out more about the Sheffield Black Atlantic Project, contact Jessica Yates: jessieyates@yahoo.co.uk or the director of the project, Dr Rachel van Duyvenbode r.van-duyvenbode@sheffield.ac.uk.