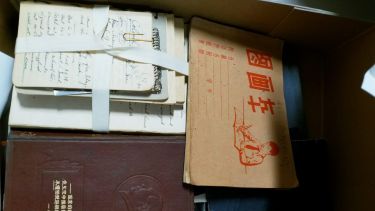

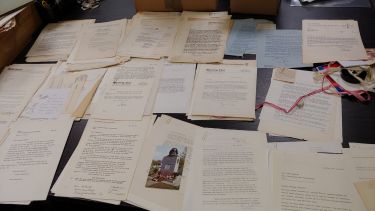

Even taken at face value, the archive of journalist Alan Winnington held by Special Collections at the University of Sheffield Library is a fascinating collection in its own right. Its 47 or so archive boxes contain first-hand accounts of the founding of the People’s Republic of China, the Korean War, as well as life in communist East Berlin, all documented within notebooks, articles, correspondence and photographs.

However, the material’s uniqueness truly becomes apparent when it is also understood that this collection – unlike contemporary material from other journalists – is delivered by a British eye-witness from a communist perspective. The Library is pleased to open the archive to researchers for the first time, providing an intriguing insight into one of the most fascinating periods of East Asian, European and Cold War history.

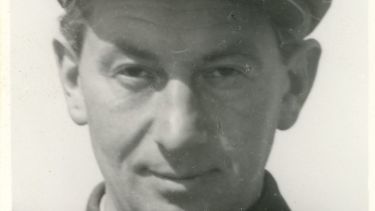

Born in London in 1910, Alan Winnington joined the British Communist Party in 1934 and by 1948 was made Press Officer. That same year Harry Pollitt, the Chairman of the party suggested he would be the ideal candidate to fulfil a request from the Chinese Communist Party Information Service for an English-speaking advisor to assist with news and propaganda. An initially reluctant Winnington then found himself an Honorary General within the ranks of the People’s Liberation Army, as the Communist forces marched into Beijing and founded the People’s Republic of China. Aside from fulfilling his advisory role to the CCP, Winnington was also able to provide reports for the Daily Worker, providing invaluable information from behind the Bamboo curtain.

When, in 1950 the Korean War broke out between the Communist North and the US-backed South, the Worker saw a unique opportunity for a British reporter to witness the conflict from a communist viewpoint and so Winnington, with Australian journalist Wilfred Burchett, were the only two Western journalists permitted to accompany the Korean People’s Army on the frontline. During the course of his reporting, Winnington witnessed first-hand the devastation caused by the conflict including the use of chemical weapons on civilians and the experience of nearly losing his own life when the jeep he was travelling in came under fire from US planes.

Two events during his time in Korea were to have a marked impact on the rest of Alan Winnington’s life, both professionally and personally. In 1950 he was taken by locals to a site in the village of Rangwul in Daejeon where he witnessed the aftermath of a massacre carried out by the South Korean government in the presence of US troops, of 7000 political prisoners. Outraged and appalled by what he had witnessed, Winnington produced a pamphlet entitled I Saw the Truth in Korea which contained his account and the photographs taken at the site and was published by the Daily Worker. The accusations that Winnington made in this publication regarding the conduct of American troops were of concern to the British government. Not only did they detail potential war crimes and atrocities, they were being made against the nation’s closest ally by a British-born communist.

As well as his regular reports on conditions during the conflict, Winnington also operated in a liaison capacity at Korean Prisoner of War camps – passing on correspondence and parcels from families to British and American soldiers and interviewing prisoners. It was his presence during a ‘re-education’ session, where prisoners were encouraged to discuss the nature of the US involvement in the war and the ultimate goal of the conflict, that led to some damning accusations from the British and American governments. MPs in Whitehall suggested that as a fully-fledged communist agent, Winnington had taken part in torture sessions, acting as an interpreter during the mistreatment and ‘brainwashing’ of prisoners. Winnington strongly denied these allegations for the rest of his life but the damage was done. He was labelled a traitor and when, in 1954 he attempted to renew his passport in order to visit home, he found it had been revoked by the British government.

Unable to return home and disillusioned by events in China during the Cultural Revolution, Winnington took the opportunity to accept the post of The Daily Worker’s ‘man in Berlin’, moving to the German Democratic Republic in 1960. In later years, as well as his regular Daily Worker (now The Morning Star) contributions, he worked as an author; writing a number of detective novels as well as continuing the travel writing which had been a staple of his career to this point (in the 1950s he wrote extensively on Chinese and Tibetan native peoples and tribes). Although his passport was reinstated in 1968, Winnington never returned to live in Britain. He died from a stroke in 1983.

In recent years, the declassification of US military documents have vindicated the claims made by Winnington in the 1950s. For Korea, this shedding of light on difficult subjects has come at a time where there is a real appetite to confront the events of the past and make amends. In 2018 the University Library was contacted by the Mayor of Daejeon. With the assistance of South Korean-based British academic David Miller, the Mayor’s office explained not only the potential importance of the content of the archive, but also the significance of Alan Winnington to the people of Daejeon, who hold in highest regard his commitment to telling the truth and the personal hardship it caused.

The archive includes Winnington’s notebooks, which contain his first-hand account of his experiences during the Korean War, as well as a large volume of photographs that he took to accompany his reports, including pictures of the massacre site in Daejeon. In collaboration with the Library, these unique photos have recently been used by local government officials and journalists to pinpoint the exact location of mass graves in the Golonggol Valley. In 2024 Daejeon intends to open a ‘Peace Park’; a memorial not only to the innocent souls who lost their lives during the Korean War but to all civilians who have suffered during global conflict. This site will feature a tribute to Alan Winnington.

The importance of archives to global collective memory and accountability is well documented; archival material is after all ‘proof’ of important events. And so the experience for the Library of discovering important untold stories and little-known world history within our collections has been humbling, even thrilling, despite the ever-present atmosphere of tragedy that such a story invokes. In the face of severe interruption caused by the COVID-19 pandemic, the Winnington Papers have been catalogued and are now open to researchers in Special Collections.

The University of Sheffield and the City of Daejeon have agreed a partnership based around the archive and there is a desire to develop a mutually beneficial relationship into the future. We hope that the opening of this archive within our care may not only help heal wounds in Korea but will contribute to a better global understanding of a turbulent time in global history.

The Alan Winnington Papers can be searched via the Library’s new archive catalogue system.

For more like this, check out our Unique and Distinctive Collections pages.