An economy of romance: Romanic fiction and financial crisis

Everybody’s got to have a hobby. Mine involves reading romantic novels (with a terrible reputation for being trashy) and every so often it also involves delivering conference papers on various aspects of these novels and attempting to explain my behaviour to rooms full of bemused academics.

I’m not quite sure why I feel compelled to do this. Part of it came out of my utter terror of public speaking, and the obvious need to get over this somehow. I had to practice, and there’s something comforting about speaking on Harlequin Mills & Boon romances for me. I know them so well. I also love them so much, I truly feel the world needs to know about them and their hidden depths.

Friday 29 April, therefore, saw me at one of the most prestigious universities in the UK (the University of Cambridge) speaking on one of the least prestigious forms of literature and attempting to convert a room full of worthy professors, doctors, associate researchers and doctoral researchers like myself, in a variety of disciplines, to an appreciation of Mills & Boon romantic novels.

The conference, hosted by the University of Cambridge ‘CRASSH’ (Centre for Research in the Arts, Social Sciences and Humanities) was entitled Art/Money/Crisis and sought to ‘question the cultural and economic position of the artwork in late-capitalist societies’ [Ref 1].

The six keynote panels, fourteen invited speakers from disciplines as diverse as literature, sociology, economics, visual arts, cultural studies and performance arts sought answers to a variety of questions including:

- How does art respond to financial crisis?

- What can art teach us about the economy?

- Can art predict, intuit, or explain the global market?

The first panel (‘Art, Money and Utopia’) commenced with several surprises, including speaker one admitting that he couldn’t stay because he was being sued at the current time and had to go back into hiding, before commencing his presentation with the admission that he had once lured the lead singer of the British rock band, Enter Shikari, into his office in order to lecture him ‘at length’ (his words) ‘the door was locked so he couldn’t escape’ (his words again) on why one of the lines from the lyrics of their song The Bank of England [Ref 2] ‘[t]hey blew up the Bank of England, the paper burnt for days’ was factually incorrect.

It may be hard to follow a start like that, but during the subsequent papers, the pace never let up. It was a programme which featured everything from replacing currency with hugs, gift economies, the rhetoric of finance in Frank L. Baum’s The Wizard of Oz and the works of Thomas Pynchon, and why several homing pigeons smuggling Cuban cigars into America from Havana, were actually ‘artists’.

Right in the middle of the programme there was the ‘Popular Fiction and Creative Writing’ research panel featuring author and PhD researcher from Lancaster University, Naomi Richards, and me, extolling the virtues of my beloved Mills & Boon romantic novels.

Now, how, you might well ask, do Mills & Boons feature in a conference like this one? Well, they actually fit rather well. Over the years I have read literally hundreds of these novels, but I have read one author for Mills & Boon more than any other: that author being Penny Jordan.

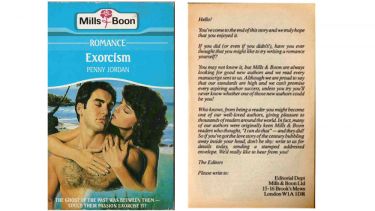

Jordan was working as a typist in Manchester when she spotted an advert much like this one which features in the back of one of her novels, Exorcism [Ref 3]:

She was just an ordinary woman, who, as the advert says, was a keen Mills & Boon reader who thought ‘I can do that’. Her subsequent books, written over three decades, chart social change from the perspective of an ordinary woman, writing for ordinary women readers.

And one cannot write for contemporary women readers, unless one understands the issues these women are facing in their lives. The theme of economic crisis, as experienced by the ordinary woman, was something that Jordan captured particularly well.

Over the course of three decades of writing, she captured the recessions of the early 80s, 90s and the financial crisis from 2008 onwards. Her heroines have had to cope with negative equity, the credit crunch, rising unemployment, cash crises, low interest rates on savings accounts, and overwhelming debt along with the rest of us.

My paper covered two of Jordan’s novels, one which dealt with the experiences of the heroine during the ‘credit crunch’ of 2008, and one which dealt with (the remarkably similar) experiences of the heroine suffering from negative equity on her home and large debts during the recession of the early 1990s.

Both of Jordan’s novels illustrate her understanding of the sense of powerlessness losing financial independence has and how it affects her characters/ordinary people in society. These are themes which will recur for her financially embarrassed heroines throughout society’s many economic ups and downs and provide an insight into the grassroots effects of sudden and unexpected financial catastrophes upon ordinary people.

My paper aimed to illustrate how these popular novels can be read as crisis literature, and, should perhaps not just be dismissed as ‘trash’ by literary critics.

On Friday 13 May, I will be speaking more about my lifelong love affair with Harlequin Mills & Boon romantic novels at the Inspire 24 hour lecture to be held in the Hicks Building. View the programme, which includes a diverse array of topics, including, most importantly, romantic fiction at 0800 hours.

References

[Ref 1] CRASSH, ‘Introduction’, Art/Money/Crisis Conference Brochure, p.1.

[Ref 2] ‘The Bank of England’; from Enter Shikari, The Mindsweep, 2015.

[Ref 3] Penny Jordan, Exorcism (Richmond, Surrey: Harlequin Mills & Boon Limited, 1985)

Written by Val Derbyshire, on 5 May 2016.