- New research published in Nature on historical sea-level rise, will give scientists new knowledge into how global warming will affect rapidly melting ice sheets in the future

- For the first time evidence shows that the rate of sea level rise in the area of Doggerland - the former land bridge between Great Britain and mainland Europe - peaked at more than a metre per century and totalled around 38 metres

- Currently sea-level rise in the Netherlands is calculated to be at approximately 30 centimetres per century, but are expected to increase

- The consequences of sea-level rise today are far more severe than in the past, due to the growth in population and the presence of infrastructure, cities and economic activity which are vulnerable to the effects of climate change

New research on historical sea-level rise will give scientists new knowledge into how global warming will affect the earth’s rapidly melting ice sheets.

The new geological data provides new insight into the rate and magnitude of global sea level rise following the last ice age, about 11,700 years ago, in a period referred to as the Holocene. This information is of great importance to understand the impact that global warming has previously had on the ice sheets and on sea level rise.

The findings are published in the scientific journal Nature by researchers from University of Sheffield, along with internal partners Deltares, Utrecht University, TNO Netherlands Geological Service, Delft University of Technology, the Netherlands Institute for Sea Research (NIOZ), University of Leeds, University of Amsterdam, Institute of Applied Geophysics (LIAG) and Bundesanstalt für Geowissenschaften und Rohstoffe (BGR).

This new knowledge into the rate of sea level rise during the early Holocene offers an important point of reference for scientists and policymakers, especially as we are now faced with a similar situation with rapidly melting ice sheets due to global warming. The research provides valuable new insights for the future.

By analysing a range of boreholes from the submerged peat layers in an area in the North Sea once called Doggerland – a land bridge between Great Britain and mainland Europe now flooded as sea levels rose due to the retreat of the ice sheets – the international team created a unique dataset to be able to make highly accurate calculations for the first time.

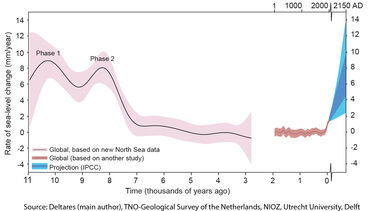

By dating the samples and applying modelling techniques, researchers showed that, during two phases in the early Holocene, rates of global sea level rise briefly peaked at more than a metre per century.

Until now there has been considerable uncertainty about the total rise between 11,000 and 3,000 years ago, ranging between 32 and 55 metres. This new study has reduced that uncertainty and it shows that the total rise was around 38 metres.

Dr Sarah Bradley, from the University of Sheffield’s School of Geography and Planning, said: “The work led at Sheffield for this project used glacial isostatic adjustment modelling to investigate how the sea levels changed and the earth responded due to the retreat of the ice sheets in the area of the North Sea once called Doggerland.

“Our dating shows that rates of global sea level rise briefly peaked at between eight and nine mm per year. For context, as a result of the current rise in greenhouse gas concentration, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) expects sea levels to rise at a similar rate between four and 10 mm per year by 2150 CE.

“Of course, the consequences of sea level rise are now far greater due to the growth in population and the current presence of infrastructure, cities and economic activity in areas that will be vulnerable to the effects of climate change in the future.”

Global sea level rose quickly following the last ice age as a result of global warming and the melting of enormous ice sheets that covered North America and Europe. Until now, the rate and extent of sea level rise during the early Holocene were not known due to a lack of sound geological data from this period.

Marc Hijma, a geologist at Deltares and the lead author of the study, said: “With this groundbreaking research, we have taken an important step towards a better understanding of sea level rise after the last ice age. By drawing on detailed data for the North Sea region, we can now better unravel the complex interaction between ice sheets, climate, and sea level. This provides insights for both scientists and policymakers, so that we can prepare better for the impacts of current climate change, for example by focusing on climate adaptation.”

The paper can be viewed at the following link: ‘Global sea-level rise in the early Holocene revealed from North Sea peats’.