Filling the silence: the powerful music of Afghanistan's exiled musicians

On the morning of August 15 2021 the flourishing musicscape of Afghanistan fell silent. As the Taliban regime came back into force, musicians disappeared and fled. Dr Cayenna Ponchione-Bailey is working with Afghan musicians now living in exile to create new platforms to share their work.

Music is something most of us take for granted. We think nothing of switching on the radio, streaming our favourite songs, buying gig tickets, going dancing or joining choirs. We can learn to play an instrument as a hobby or choose to make a career out of it. But what if this was all taken away?

Throughout the 1970s to the 1990s, war turmoil and repeated invasions in Afghanistan led to reduced music creation across the region. In the late 1990s all forms of musical expression, public or private, were brought to an abrupt halt when the Taliban seized the capital, Kabul, for the first time and gained sudden control of two-thirds of the country. As well as television and cinema, they immediately banned all music, destroying instruments and punishing those found with musical paraphernalia, with the belief that it was sinful and immoral.

After almost a decade without music, the fall of the Taliban in November 2001 saw the return of musicians from exile. Radio and television stations reappeared with live performances fewer than 48 hours later.

Over the following two decades, Afghanistan would steadily rediscover its rich and varied musical heritage and traditions. Live music returned and many engaged with its diverse musical styles influenced by Persia and India, the country even saw a rise in the development of specialised music educational programs for children. Young composers, conductors and musicians became part of a new era of orchestral music-making by developing new repertoire for ensembles.

But in the late morning of August 15 2021 the flourishing musicscape fell silent once again. As the Taliban regime came back into force, musicians disappeared and fled through fears of being harassed, brutalised or murdered for their craft.

Dr Cayenna Ponchione-Bailey is a Leverhulme Early Career Research Fellow in the Department of Music. Her research is focused on documenting the historical and contemporary activities of the Orchestras of Afghanistan as well as their social and political significance. Combining this research with her role as Conducting Fellow of the Oxford Philharmonic Orchestra she is collaborating with musical colleagues now in exile to create opportunities for musicians and composers of Afghanistan to have their music and voices heard.

A 24 hour turn around

Since her first visit to Afghanistan in 2018, Cayenna has worked closely with musicians at the Afghanistan National Institute of Music in Kabul tutoring young conductors and composers online. With an academic background in the social psychology of orchestral performance and a profound interest in the intersection of music and social justice, she organised the UK residency of the Zohra Orchestra, the first all-female orchestra in Afghanistan, in 2019.

This collaboration led to a Leverhulme project that would see her return to Afghanistan for a prolonged period of time. But work on the early stages of this project was halted as soon as it began when Kabul was captured by the Taliban on 15 August 2021.

“When Kabul fell everything went up in smoke. The lives of many individuals were compromised and all music was immediately shut down. Using our international network, we immediately began humanitarian work to find ways to get musicians out of the country safely. We created an informal organisation called the International Campaign for Afghanistan’s Musicians to lobby, fundraise and pool resources together. It was only in that December that many of the musicians I knew were finally able to find safe passage to other countries, and that is a small proportion of the number of musicians in Afghanistan, most of whom are still in the country” explains Dr Ponchione-Bailey.

The research project used to be called ‘The Orchestra in Afghanistan’ but this of course has had to be changed as there are no orchestras left in the country

Dr Ponchione-Bailey

Leverhulme Early Career Research Fellow in the Department of Music

The Orchestras of Afghanistan

Following some additional funding from Research England, Cayenna was able to restructure her project. She designed a participatory research project and created a Research Stakeholders Group of musicians and musical scholars now exiled from Afghanistan.

“It has been incredibly stimulating to work with the nine members of the Research Stakeholders Group over the past six months. Bringing together Afghanistan’s top musicologists, composers and practitioners of orchestral music to have critical discussions about research priorities and audiences in this new world order has been absolutely transformative” says Cayenna.

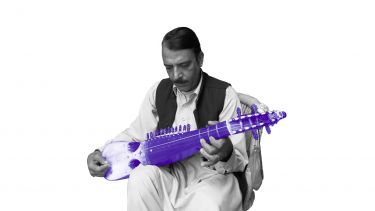

With her conductor’s hat on, Cayenna also worked closely with Afghan pianist and composer Arson Fahim to co-curate a complete concert of new orchestral works, commissioning new compositions and arrangements of traditional Afghan songs (with support from University of Sheffield HEIF AHKE grant). The works build on the instrumentation of orchestras at the Afghanistan National Institute of Music prior to the Taliban take over in 2021. The compositions are written for an orchestra comprising both traditional Afghan instruments, such as the rubāb, dutār and tablā and those of European heritage, like the violin, trumpet and clarinet.

The concert took place at the Spitalfields Music Festival in London, where a British orchestra performed a complete programme of Afghan orchestral music for the very first time.

Celebrating Afghanistan’s rich history of orchestral music-making, the Oxford Philharmonic Orchestra and guest musicians including; Saphwat Simab (Afghan rubāb), Shahbaz Hussain (tablā), Yusuf Mahmoud (harmonium), William Rees Hoffman (Herati dutār) and Mehboob Nadeem (sitār) performed compositions to showcase the talent of the country’s exiled composers and musicians.

The works of nine Afghan composers were performed and eight of these nine were world premieres, specially commissioned for the concert. The works included original compositions, and arrangements of traditional Afghan songs by Milad Yousufi, Qambar Nawshad, Arson Fahim, Elaha Soroor, Ghafar Maliknezhad, Mohsen Saifi, Meena Karimi, Qudrat Wasefi and Zalai Pakta.

“It was both thrilling and heart-breaking to be organising this concert with composer and pianist Arson Fahim. Thrilling, because it is wonderful to be bringing this vibrant and unique orchestral practice to the UK and to be supporting the creative work of Afghanistan’s musicians while they are in exile. But heart-breaking, because this music should be able to be heard in Afghanistan, and that is currently not possible” says Cayenna.

“This concert was about sharing the beauty of Afghanistan and its music but also raising awareness about the sad realities the country is facing. The concert is a way of keeping the sound of Afghan music loud and alive – a symbol of resistance and a message of hope” adds Arson Fahim.

Looking ahead

Following the success of the performance at Spitalfields Music Festival, Cayenna is working with the Oxford Philharmonic Orchestra to organise a second performance in the Sheldonian Theatre in Oxford. A screening of the performance of Elaha Soroor’s composition is also in the works with the University of Sheffield’s Concerts Team.

The Research Stakeholders Group continues to meet and are working to produce a collaborative book project. Drawing on existing research, historical documents, collective memory, and the recent experience of practitioners, the collectively authored chapters will bring together knowledge about the orchestral music and musical practices of Afghanistan into a single volume for the first time.

For the Research Stakeholders Group, this is an essential step in ensuring that this knowledge is able to be passed along to the next generation of Afghan musicians.

Meanwhile, musicians still in Afghanistan are facing increasing hardships and Cayenna’s work with the International Campaign for Afghanistan’s Musicians is ongoing. The group raises funds to support basic life needs of musicians still in the country, and works to raise awareness about their vulnerability —encouraging international governments to offer asylum to those still seeking safety.

“We’ve had reports of our colleagues still in Afghanistan who have been picked up, had their phones looked at, taken away, beaten up and imprisoned for days before being released back home. It has been a year since professional musicians, particularly hereditary musicians who have known little else in their lifetimes, have been able to work. Their families are slipping into destitution with significant consequences for children’s health due to malnutrition. The situation is genuinely dire for many people at the moment and compounded by the horrific war on women’s rights” explains Cayenna.

“It's important to ensure that the voices of Afghan musicians continue to be heard. Our collective work is focused on ensuring not only the survival of Afghanistan’s orchestral musical practices, but that they, and the musicians and composers themselves, continue to flourish while music is censored in their home country. For so many of the Afghan musicians and composers that I work with, music is a particularly important mechanism for expressing their messages of social justice, gender and ethnic equality, personal liberty, and freedom from violence and oppression. We will keep working to find and leverage available platforms in the UK to amplify these voices and produce a narrative of unity, peace, compassion and mutual understanding” she adds.

Written by Alina Moore, Research Communications Coordinator