A new tool for inclusive participation in primary care research

Clinical research should reflect the diversity of our society, but that’s not always the case. Researchers at Sheffield have developed a powerful geospatial mapping tool to help recruit more diverse and representative research participants in the region.

Often dubbed the ‘front door’ of the NHS, primary care includes a wide range of health services we use daily, such as GP practices (in- and out-of-hours), community pharmacies and sexual health services.

With 90% of all NHS consultations taking place in primary care settings – that’s 300 million GP consultations each year compared to 23 million A&E visits – it has been said that ‘if general practice fails, the NHS fails’.

Clinical research is essential to ensure primary care services provide the best care for their communities. To do this well, research projects must incorporate people from all walks of life. But a longstanding problem has been equality, diversity and inclusivity (EDI) in patient recruitment and participation, leading to unrepresentative results that risk structural bias in the health system.

With support from the University of Sheffield’s Enhancing Research Culture fund, and in collaboration with Primary Care Sheffield and Sheffield City Council, a project team headed by Dr Jon Dickson has developed a two-pronged method of data and engagement for equal, inclusive and diverse primary care research.

“Most clinical research in the UK tends to only reach the most affluent, most capable, least challenged segments of society, and tends to exclude people who are deprived, people from ethnic minorities and people with disabilities,” Dr Dickson explains.

“An inclusive approach is much more complicated than the traditional way, where you just recruit the able, willing people who've got no barriers to taking part in research.

“You need to think very carefully about the characteristics of the people you want to recruit so that, at the end of the study, you've got a representative population included in the project.”

For primary care researchers, then, there are some pressing issues to address: What are the barriers to taking part in clinical research and how can we remove them? And, how can we create a research culture where EDI is embedded at all stages of the research process?

PRiD3: A data-driven approach to EDI

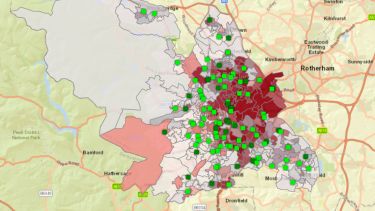

To enable clinical researchers to recruit more diverse and representative groups of participants the team developed the PRiD3, a powerful geospatial mapping software tool.

PRiD3 allows researchers to map the Sheffield region by ethnic group, deprivation and disease prevalence, cross-reference these characteristics with population density and geographical area, and then work with local primary care sites to contract patients whose background and health needs are relevant to their project.

The team is using PRiD3 to locate areas with high density of people from the Somali community so that they can invite them to take part in the CognoSpeak study, where a ‘digital doctor’ asks questions to patients in order to differentiate dementia from other memory complaints.

Community outreach and engagement

But data can only go so far.

“In order to engage people in research you need to have a relationship with them,” says Dr Dickson.

“Sometimes it's as simple as the logistics of how we’re going to approach, say, 2,000 people with invitations to take part in research. Should it be by letter, by text or by phone call? Other times much deeper challenges, such as language barriers; some people don't speak English, but services tend to be led by English-speaking people.

“Even deeper than that are quite important cultural issues. Historic mistrust, for example, where there may be good reasons for particular groups to mistrust powerful organisations.”

Alongside the development of PRiD3, and together with local charities and patient advocacy groups, the team launched an outreach and engagement programme. This provided a forum where patients could raise their own agendas and lived experiences, and it facilitated research co-production between the team, healthcare organisations, and collective and individual patients.

“The Primary Care Sheffield engagement team had lots of really interesting productive discussions with a whole range of community groups about their experience of research, their preferences for research projects, the kind of thing that they would like to get involved with, and the kind of things that they see as barriers.”

In the CognoSpeak study, for example, the CognoSpeak team collaborated with Israac, a local Somali community association. Together they held a series of workshops to explore the barriers to seeking help from primary care and to taking part in dementia research, and how Somali people, and other ethnic communities across the city, can be included in research.

Plans for the future

“The [Enhancing Research Culture] grant was a very important part of developing our ideas and the technology,” says Dickson, “but I think one of the challenges with EDI work is to extend it beyond research project time windows. We're looking for ways to carry on where we left off.”

The team are working to secure further funding to further develop PRiD3 and encourage its use more widely across the region. Also in the pipeline is a Sheffield NHS Family EDI microsite, a ‘one-stop shop’ where people from ethnic minority and under-served communities can find opportunities to participate in health research in Sheffield.

EDI by design

Reflecting on the project, Dr. Dickson is a firm believer that diverse, equitable and inclusive outputs can only come from a diverse, equitable and inclusive research process.

“One of my big takeaways is that EDI needs to be thought about right at the design stage of research. It can't be retrofitted. You need to sweat the small stuff early, think hard about the details of research delivery right when you first put pen to paper, define your research question and start to design your research methods.

And it needs to be done with reference to people who have expertise on the ground. You need to understand your population because every city is different, and every region of every city is different.”